During my ten-year stint in the Paul deLay Band, we worked on dozens of Paul's quirky, brilliant, original songs. But the one we worked the longest and hardest on—by far—was “Remember Me.” Week after week in early 2001, we'd assemble in my Gresham garage and play the song—never to Paul's satisfaction. It wasn't that he didn't know what he wanted. The song had come to Paul in a dream, nearly fully-formed. But that was the challenge: to make it sound just as it had in that dream—haunting and ghostly. Ostensibly, the song was in the voice of Paul's late mother, who had come to him in the dream, wishing to be remembered. But at one point Paul confessed to us that the song was also about his own wish to be remembered after he was gone. Paul needn't have worried on that account: none of us who knew and worked with Paul deLay—or even just heard his music—is likely to forget him.

"In Remembrance Of Paul deLay," by Diane Russell

I first met Paul a year or two before his infamous 1990 drug bust. My first keyboard teacher, Seattle organist Norm Bellas, had called to invite me to hear him audition with the Paul deLay Band at a Portland nightclub. I'd never heard of Paul; although I'd been living in Portland for a few years at that point, I'd stayed away from the music scene. After years of dealing with greedy clubowners, drug-addicted fellow musicians, and the general grind of trying to make a living playing music, I'd gotten seriously burnt out. I kept wondering what might have happened had I pursued my other early dream: becoming a professional writer. So I'd moved north and enrolled at PSU, living off a small allowance offered by my grandparents. I'd kept my nose to the grindstone, getting straight “A's” and staying away from musical temptations. Still, hearing Norm play with a local blues band sounded like fun, so I ventured down to the club.

Norm Bellas

On hearing Paul, I was very impressed. He was a bigger-than-life presence—not just in physique but in personality. But what really stood out to me was that unlike most white bluesmen, Paul made no effort to ape black artists; he was undeniably soulful without being affected. Still, it isn't like a white light came down from the heavens, accompanied by a booming voice telling me to forget about journalism and join the Paul deLay Band. Even though Norm didn't get hired, it never crossed my mind to try out myself. I didn't even go out and hear the band again. However, the bass-player, John Bistline, had mentioned that he played golf, and we became regular golfing buddies. And soon after Paul got busted for drug trafficking, John urged me to join the band. (With Paul's bust, the keyboard player, Tippie Hammond, had quickly departed.)

At first, I said, “no way.” I explained that one of the main reasons I'd given up music was that I hated working with drug addicts. But John replied that the deLay Band was about to become the cleanest band around. Paul's had been a federal bust, and the feds would be watching the band—even drug-testing its members—for months to come. Further, John said that the gig would just be temporary—playing out the band's calendar until Paul was incarcerated. So what did I have to lose?

John had a point. I'd graduated from PSU with high honors, winning the undergraduate Historical Writing Award, but I'd yet to find any work as a writer. So why not play a few gigs with the deLay Band? I'd have some fun, make some money, then get back to the journalism job-search. So I said, “OK.”

The "audition" consisted of showing at the band's next gig—at the Cascade Bar & Grill in Vancouver—and playing with the band. I was rusty, and I didn't have a real organ (my two B-3's were still in storage in the Bay Area). But after playing a few tunes on my Korg CX-3 (an analog precursor of today's digital “B-3 clones"), Paul said, “You can boogie-woogie just fine!” That was that: I was a member of the Paul delay Band.

l to r: me, Jeff, Peter, Paul, Dan, & John

I then set to work learning the band's book. Not that there actually were any charts; I was just given a couple of old albums and a recent live cassette tape. Most of the material was classic blues covers, but there were a couple of intriguing originals on that cassette. Truthfully, the playing and arranging didn't knock me out—it was sloppy to my ears—but the songs were interesting, especially a haunting ballad, “Why Can't You Love Me?”

Re/ that sloppiness: during the first break of my first actual gig with the band—at Portland's Belmont Inn—Paul took me aside and said, “Bubba [he generally called guys “Bubba” and women “Sis”], I know you're a tasteful player and all, but this just isn't working for me. I'm used to the keyboard player throwing up a wall of sound!” I replied, “Paul, I'm not a 'wall of sound' kind of guy. I think the music needs space to breathe. That wall of sound has been keeping people from hearing how good you are.” Paul wasn't particularly pleased with this answer, but he dropped the matter for the time being.

The truth was that for all his talent, Paul was insecure. In part, his desire for the keyboards to erect a "wall of sound" was so that he had something to hide behind. But it was also consistent with his general tendency to desire a lot of everything. As I would come to learn, the concept of "less is more" was entirely foreign to Paul deLay (at salad bars, he'd famously pile on ALL the dressings because he couldn't bear to leave any of them off). But again, as I'd already sensed, Paul had been hiding behind that “wall of sound.” All the space I was introducing to the band was scary to him; as he admitted, it made him feel naked up there. But to me, that was the way the music should be. Paul's model was raw, authentic Chicago blues, which featured a lot of emotion & spontaneity but also, often, plenty of clashing & clutter. I'd listened to Chicago blues as a teenager—even seeing greats like Muddy Waters & Buddy Guy at San Francisco's Fillmore Auditorium—but I'd been more influenced by Memphis soul music, a more spare, organized style characterized by repeating, interwoven rhythmic “parts” played by guitar, keyboard, and horns.

Fortunately for me, saxophonist Dan Fincher, the other new member of the deLay Band, had a similar background & concept to my own. Dan had actually played with Paul before—in the seminal white NW blues band “Brown Sugar.” But Dan also had a lot of experience in & and affinity for soul music, and he loved to create & play “parts” or “riffs.” Long-time deLay Band guitarist Peter Dammann was a Chicago blues guy through and through—he even grew up there—but he was interested in soul music too. Quickly, Pete fell in playing parts with Dan and me, particularly on Paul's new original material—most of which didn't bear much relationship to Chicago blues to begin with.

The aforementioned “Why Can't You Love Me” was the song on which the new Paul deLay Band's sound really came together. During the intro and verses, I started playing a repeating 2-bar riff (using the chords made famous by Miles Davis' “Freddie the Freeloader”). But I noticed that Dan was playing a different riff. When I pointed this out to him, he said he'd switch to what I was doing. But I liked Dan's idea too, and it occurred to me to alternate the two parts. That made for an interesting four-bar riff that created just the right haunting mood for Paul's lyric and harmonica playing. Pete picked it up, and we all agreed we had something cool and unique. Soon, on other songs, we went even further, adding harmonica as a fourth voice to some of our ensemble parts. Paul, who despite his Chicago blues purism as a player had eclectic tastes as a listener (he even loved the Lawrence Welk Show!), began creating great riffs for his tunes—often coming up with them before he had lyrics. (He'd invariably play them to us without a count-off, creating general confusion.) Paul welcomed input from band members on his songs, and I was able to contribute a lot. The absent “wall of sound” was never mentioned again!

By November, 1990, the band was in the studio, recording “The Other One”--featuring all original material, much of it brilliant. Paul had been toying with songwriting for years—especially lyrics—but due to his insecurity he'd kept his songwriting under wraps, only recording a couple of original instrumentals. In the wake of his embarrassing drug bust, though, Paul was freed up. After his “perp walk” had been plastered across the front page of The Oregonian and led the local news broadcasts, Paul was past worrying about what people might say about his songs.

Paul's perp walk

In fact, “The Other One” received nothing but raves, both locally and beyond. "Why Can't You Love Me" won the Portland Music Association's '91 songwriting competition in the blues category. Reviewers found the CD as a whole to be a breath of fresh air—simultaneously clever & soulful, and free of blues cliches. Those were fun, exciting times. Paul, Pete, Dan, John, drummer Jeff Minnick, and me enjoyed playing together. Just as importantly, we got along well off-stage as well—a challenge for bands that log a lot of miles on the road.

I have so many funny memories of those days, like the time John literally rode his big bass amp down a club's staircase, the time we froze in a Wintrop hotel--playing golf down the hallways to keep warm--and the time we played a prank on Paul, slipping on Paul deLay masks on stage. (When he turned around and saw us, he did a memorable double-take). The group was unusually democratic; we split the money evenly and the work as well. Paul would lug gear just like the rest of us—often picking up one of the huge Peavy p.a. speakers we traveled with and carrying it across the club by himself. His only perk, as the band's “star,” was to always have his own motel room. My “temporary” stint in the Paul deLay Band had stretched out past two years as the legal process played out, but that was fine with me. Thoughts of returning to that journalism job-search were gone; I was once again hooked on playing music.

The early '90s deLay Band had a lot of fun on the road One of the infamous Paul deLay masks

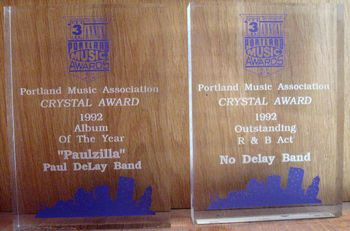

However, Paul's legal situation still hung over the band. He hadn't actually been a drug trafficker--just a user who'd agreed to make a few deliveries for his dealer in exchange for having his debt forgiven. But the Feds were determined to throw the book at him: ten years in a federal prison without hope of parole. (This was during George Bush's "War On Drugs," when busting celebrities was a priority.) When Paul's attorney advised him to accept a plea deal, we all felt a sense of urgency to record a second CD before the hammer fell. So in the spring of '92 we returned to the studio and quickly recorded “Paulzilla.” This CD also featured all-original material save for one cover: a poignant version of Guy Massey's “The Prisoner's Song.”

Paul's final pre-incarceration gig was @ Bojangles in Portland

Paul was incarcerated for nearly three years—from May, '92 to January, '95. Before going in, he'd urged us to keep the band together, suggesting that we get soul singer Linda Hornbuckle to front the band in his absence. When we dubbed the interim group, “No Delay,” Paul had a good chuckle. In fact, No Delay was a powerhouse band in its own right, and the CD we recorded, “Soul Diva Meets the Blues Monsters” got rave reviews of its own, both locally and nationally. One reviewer wrote, "The most beautiful and powerful blues/gospel/soul voice in the Northwest, backed by the tightest and most talented band for the ultimate Double-Whammy."

l to r: Ben Jones, Dan, Linda, Pete, Brian Foxworth, & me

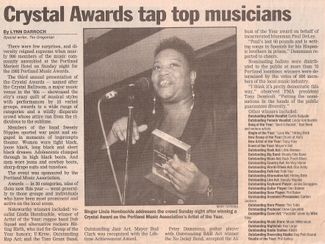

Both the Paul deLay Band and the No Delay Band won Portland Music Association Crystal Awards in '92

Linda won the '92 Crystal for Artist Of The Year

We had a ball playing with Linda Hornbuckle--truly a powerhouse vocalist--for three years. But No Delay's material was exclusively covers, and Paul had written some brilliant songs while incarcerated. So on Paul's release from prison, Pete, Dan, and I were excited to reunite with him. The band's two-night return gig at Bojangles in late January, 1995 was big news in Portland; it was the subject of an Oregonian headline and feature, and crews from all four local news stations broadcast live from the club. When Paul triumphantly sang, "I Win," there wasn't a dry eye in the place.

Paul and I (accompanied by our cat Alex) worked on his new songs soon before his final release from prison

Anticipation was high for The Paul deLay Band's return gig... ...and fans weren't disappointed!

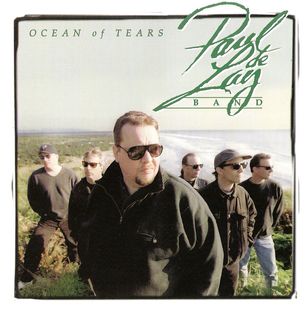

By the fall of '05 we were back in the studio, working on a new CD, “Ocean of Tears.” The stakes were high; the band had been signed to a record deal with Evidence Records, and the label was expecting something special. They weren't disappointed. Paul had spent his time in prison productively; writing songs had been an outlet for his pain & frustration, and he'd had time to develop his songs more fully than ever before. Paul had assembled a prison band, made up of beginning musicians to whom he'd laboriously taught the ideas he had in his head. He'd even gotten around a ban on cassette recorders, managing to smuggle out a crude tape of some of the songs. All we had to do with those songs was polish them a bit.

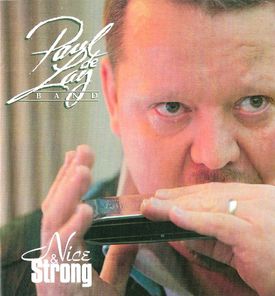

Other songs on “Ocean Of Tears”—especially the more funky, rhythmic material--required a bit more input from the group. But that was up the alley of this version of the deLay Band, which included a new rhythm section: John Mazzocco and Mike Klobas. John and Mike were veterans of two of the NW's top blues bands—Curtis Salgado & the Stilettos and the Lloyd Jones Struggle, respectively--and both bands had featured plenty of original R & B material. The marriage of Paul's prison-inspired & polished songs and his new band resulted in, arguably, the best CD he ever recorded. Certainly, the critical response—both local and national--to “Ocean Of Tears” was overwhelmingly positive. Likewise, the band's follow-up CD, “Nice and Strong” (1997) generated plenty of buzz. In addition to our usual NW gigging, we made trips to LA and the Bay Area, to the east coast, Chicago, Florida, and even to Norway. Everywhere the band went, people were blown away.

Poster from the '97 Notadden Blues Festival The Paul deLay Band at San Francisco's Fillmore Auditorium

Clowning backstage at the Fillmore Megan deLay (left) and my wife Tracy had plenty of fun at our gigs

The Paul deLay Band at the '97 Mt. Hood Jazz Festival

My personal and musical relationship with Paul was great during this period. We'd often ride to and from gigs together, and we loved to listen to gospel music on those drives--or to classical when we'd heard one too many “blue notes” that evening. (When traveling with the rest of the band, books-on-tape were the order of the day.) By this time, Paul had married the love of his life (and inspiration for many of his songs), Megan Gill, so we didn't hang out much. We never really had. But we talked frequently on the phone, and Paul would invite me over when he was working on a new song.

Paul had a cheap little Casio keyboard on which he'd play the outline of the song for me. I'd suggest some possible alternative chord progressions or arrangement ideas. If there was something familiar about the tune, Paul would want to hear about it; he had a virtual phobia for anything cliche'd. (I nearly broke his heart one time when I said that the bridge to his latest song was the same as the bridge to “When a Man Loves a Woman.”). If my contribution to a song was significant, Paul would insist on giving me a songwriting credit—this above & beyond the 50% of each song's publishing that Paul gave to the band on general principal.

This was generous on Paul's part, but also fair, because in fact everyone in the Paul deLay Band contributed to the songwriting. No one touched Paul's lyrics; Paul didn't want or need feedback in that department. Paul was one of the wittiest people I ever knew, and his lyrics reflected that. Sometimes poignant and often hilarious, they were pure Paul! But at rehearsal, the musical aspects of Paul's songs would be kicked around and ideas would flow freely. We'd each argue for our ideas, but usually not too stridently. We all felt that presenting ideas to Paul and letting him pick & choose among them was the way to make the songs come out coherent and sounding like Paul deLay songs. We basically filtered our ideas thru Paul, and that approach worked.

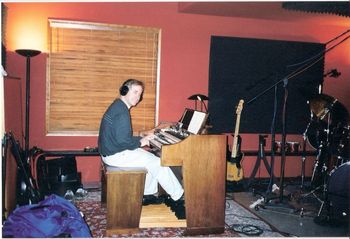

Paul deLay Band rehearsal at my house, January, 1995

Really, the band was very harmonious for the first couple of years after Paul's release. But fissures gradually began to develop that would eventually cause the band to break apart. Some of those problems stemmed from outside pressures and influences. For instance, as great as the critical response to “Ocean Of Tears” had been, CD sales outside of the NW were weak. And Paul kept hearing from—and listening to--blues purists who said he should be playing & recording traditional blues. Meanwhile, we band members had grown increasingly concerned about Paul's weight, which had ballooned to around 500 lb. No longer would Paul pick up heavy gear and carry it across a room. Just walking across a room would leave him gasping for breath.

Paul had beaten his cocaine addiction, but he'd replaced it with an even tougher habit to kick: overeating. Paul had always loved food; when viewing our road itinerary, he'd enthusiastically plan out what he'd eat at what restaurant or deli in each town. He'd even rub his stomach and say, "delicious!" when one of us played something he liked! But like most addictions, Paul's food obsession was progressive, and by the late '90s it had become life-threatening.

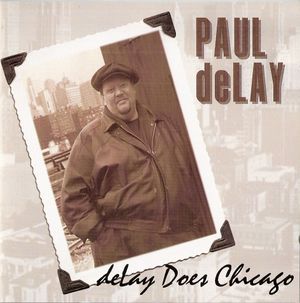

Things came to a head when the band attempted an intervention during a band meeting (at a delicatessen, appropriately enough). Paul didn't react well, saying at one point, “I'd rather die than go to an Overeaters Anonymous meeting.” At that moment we all knew, on some level, that the band's days were numbered. The first step in that splintering was Paul's recording the penultimate CD of his Evidence Records contract with a group of young blues musicians he'd heard in Chicago. With that CD, 1999's deLay Does Chicago, Paul succeeded in momentarily appeasing the blues purists, but at the cost of alienating his band. Had Paul recorded with a group of Chicago blues greats, we'd likely have accepted the recording as being good for our band. But despite a strong performance from Paul, 1999's deLay Does Chicago clearly wasn't in the same class as the deLay Band's releases. It felt more like Paul lashing out at us for our attempted intervention and other grievances. (He was even more angered when we refused to help him develop the material for the Chicago CD.) Soon after, John left the band, followed a year or so later by Mike. By the end of 2002, Dan and I were gone as well.

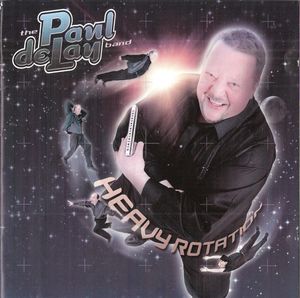

John's departure did lead to an interesting and challenging phase for me: playing organ bass in a traveling blues band. Paul enjoyed the change of pace, saying it freed him up musically. And I enjoyed reworking my approach to Paul's material, with my keyboard parts now simplified and integrated with bass lines. With Kelly Dunn on drums, we went into the studio a final time in the spring of 2001, recording “Heavy Rotation.” We were more than a little concerned with how reviewers would react to the bass-less sound of the recording, but the response was all positive. (The Living Blues reviewer wrote, “Pain's left hand carries the bass for the entire CD and is truly to be marveled at.”) But without question, the deLay Band was no longer the powerhouse it had been a few years earlier.

In "Heavy Rotation," Paul poked fun at his own girth Recording overdubs on "Heavy Rotation"

The "Heavy Rotation" band: l to r: Kelly Dunn, Dan, Pete, me, & Paul

Other issues aside, Paul and I were growing apart musically. He continued to question his non-traditional blues direction. The critics had raved about our fresh, innovative sound, but in a music industry that was increasingly compartmentalized, there wasn't much of a market for genre-crossing acts. Plus, Paul simply missed playing Chicago-style blues. At the same time, I'd begun returning to my own musical roots, namely soul music and soul-jazz. I'd been playing a regular Thursday night soul-jazz gig with former Motown drummer Mel Brown at Portland's Jimmy Mak's for years. Now I was branching out more, playing side gigs with visiting musical legends including Bernard Purdie, Solomon Burke, Howard Tate, the Shirelles, and Bo Diddley. I always tried to “bring it” when playing with Paul, but he couldn't help but notice that I was more excited about those side gigs than I was about my gigs with him. Paul's writing had ground to a halt and our performances had become increasingly rote.

With Howard Tate @ Safeway Waterfront Blues Festival The Mel Brown B-3 Organ Group

With Solomon Burke (& his daughter) With Bo Diddley (center) & Carlton Jackson

Finally, at another deli band meeting (in December, 2002), Paul asked—not for the first time--if I would start playing piano as well as organ on our gigs. He explained that he'd been playing some side gigs with a blues piano player and he was really getting back into that sound. I enjoyed playing piano as well as organ, but I was already lugging a cut-down B-3—complete with bench and bass pedals—along with a Leslie Speaker and a bass amp to our gigs. There was just no way I was going to add a digital piano & keyboard amp to that rig! So Paul announced then and there that he was going to make a change: replacing Dan and myself with a piano player & bass player. There was no arguing; really, the split was pretty amicable.

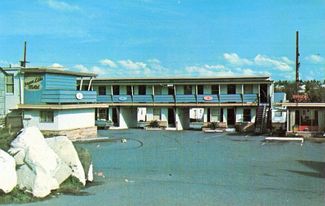

In truth, I was relieved. From a musical standpoint, I knew it had been time to move on for awhile. But I also knew that I'd miss not only the financial security of working in the deLay Band but also the comraderie. When you play in a touring band for ten years (not counting the three No Delay years), you become a family. OK, a sometimes dysfunctional family. But a family nonetheless. After all, you spend much more time with your bandmates than you do with your wife or girlfriend. And out there on the road, you depend on each other; it's kind of “us against the world.” The deLay Band had shared countless experiences: long drives, cheap motel rooms (some so odoriferous we wouldn't eat or walk barefoot in them), great gigs & crummy ones, broken vehicles & p.a. systems, rehearsals & recording sessions, meals, etc., etc. We'd told each other the same stories so many times that we'd bleat out an “alarm” when one of us launched into an all-too-familiar tale! As excited as I was to leave the deLay fold and begin the next phase of my musical career, the change was bittersweet.

One of our "home-sweet-homes" on the road: Seattle's odoriferous Green Lake Motel

In the ensuing years, Paul and I didn't socialize, and we only played together on two or three occasions. But when we did bump into each other, we were always friendly. I'd ask about Paul's health (he'd long suffered from migraines, joint pain, and sleep apnea), and Paul would ask how me and my wife Tracy—who Paul fondly called “Tracyhead” or "Tracyface"--were doing. In 2005, Paul caught my first Waterfront Blues Festival set with King Louie & Baby James, and he was very complimentary. It took awhile, but I eventually got out to hear the organ & sax-less version of Paul's band, and we hung out and had a good time together. Sometimes Paul would hear a joke that was too good to keep and he'd leave it on my answering machine.

When Tracy called downstairs to me one afternoon in 2007, saying, “Paul deLay is dead,” I was instantly devastated. We'd always realized that Paul's weight was problematic. Paul himself had once quoted his doctor as saying, “there's old people and there's fat people, but there's no old fat people.” But this was out of the blue. As I soon learned, Paul had felt under the weather following a road trip to Mexico and had checked himself into the hospital for testing. Mere days later, he was dead from leukemia. The cold reality hit me: my friend and musical collaborator was dead at the age of 55.

Paul deLay memorial/benefit, Aladdin Theater, April, 2010

That was six years ago, but I still think of Paul often. Sometimes it's a phrase from one of his song lyrics. Sometimes it's a remembered joke or incident. Most of the time, the memories are more pleasant than sad. But I still can't listen to the CD's we recorded together without getting the blues. Last year, playwright Wayne Harrell invited former deLay band members and their spouses, along with Paul's sister and widow, to a read-thru of “DeLayed," a play loosely based on Paul's life. What we didn't realize was that, for this run-thru, Wayne intended to play tracks off our CD's—a lot of them. That part wasn't pleasant for any of us. It's one thing to have thoughts of a friend or family member who's passed away—even to view photos of him. But to hear him singing his heart out—at the peak of his vitality and creativity—that's truly painful, particularly when he died far too young.

Still, I'm grateful for those CD's. I'm very proud to have contributed to something so soulful & original—something that has entertained, influenced, and even inspired people around the world. Paul wanted to be remembered, and thanks to his recordings I believe he'll be remembered for a long, long time.

Addendum: Back in 1997, the Paul deLay Band performed at the Notodden Blues Festival in Norway. Twenty years later, in 2017, we discovered and released a live recording of that performance, "Live at Notodden '97." By happenstance--or some cosmic convergence--this came 10 years after Paul's death. The CD--capturing Paul and the band at our peak--received rave reviews in the US and overseas, and was nominated for a Blues Music Award in the "Historical Album" category.